Tooth development, Eruption and Related Difficulties

On 01-11-2020 | Read time about 7 Minutes

Tooth development

Tooth development progresses through well-defined stages – epithelial thickening, bud, cap and bell.

Tooth germs develop from the dental lamina, which develops from the primary epithelial band. The dental lamina forms a series of epithelial buds that grow into surrounding connective tissue. The buds are associated with a condensation of mesenchyme and together they represent a tooth germ at its early ‘cap’ stage of development.

The epithelial bud becomes the enamel organ and the mesenchymal cells- the dental papilla and follicle. The cells at the margin of the enamel organ grow to enclose some mesenchymal cells, the ‘bell’ stage of development.

Histodifferentiation of the enamel organ now forms the external and internal enamel epithelia, stratum intermedium and stellate reticulum. On the lingual aspect of each primary tooth germ, the dental lamina proliferates to produce the permanent successor tooth germ. Permanent tooth germs with no primary precursors are produced by distal extension of the dental lamina. Dentine formation occurs after differentiation of dental papilla cells into odontoblasts, which is induced by the internal enamel epithelium.

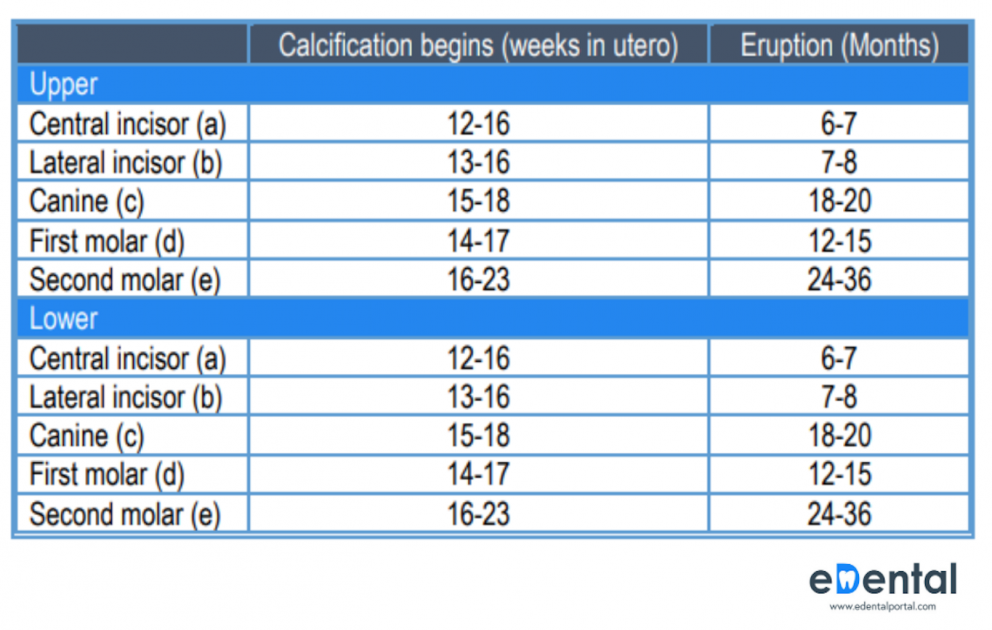

Once dentine formation has begun, the adjacent cells of the internal enamel epithelium differentiate into ameloblasts and produce enamel. The dentine of the roots of teeth is produced in a similar fashion by differentiation of odontoblasts induced by the internal enamel epithelium, and root growth is controlled by the epithelial cells at the margins of the enamel organ – the root sheath of Hertwig. Root growth is not complete until 1–2 years in the primary dentition and 3–5 years in the permanent dentition after eruption of the crowns of the teeth. The beginning of mineralisation for both dentitions is given in the tables below.

Eruption

The time of eruption of both primary and permanent teeth varies greatly. Variations of 6 months on either side of the usual eruption date may be considered normal for a given child. Moyers stated that the most common sequence of eruption of permanent teeth in the mandible is first molar, central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first premolar, second premolar, and second molar.

The most common sequence for the eruption of the maxillary permanent teeth is first molar, central incisor, lateral incisor, first premolar, second premolar, canine, and second molar. These common sequences are identified in each arch to be favourable for maintaining the length of the arches during the transitional dentition. It is desirable that the mandibular canine erupt before the first and second premolars. This sequence aids in maintaining adequate arch length and in preventing lingual tipping of the incisors, which not only causes a loss of arch length but also allows an increased overbite to develop. An abnormal lip musculature or an oral habit that causes a greater force on the mandibular incisors than can be compensated for by the tongue allows the anterior segment to collapse. For this reason, use of a passive lingual arch appliance is often indicated when the primary canines have been lost prematurely or when the sequence of eruption is undesirable.

TEETHING

In most children the eruption of primary teeth is preceded by increased salivation, and the child will want to put the hand and fingers into the mouth—these observations may be the only indication that the teeth will soon erupt. Some young children become restless and fretful during the time of eruption of the primary teeth. There is no scientific evidence that teething does increase the incidence of infection, does not cause any rise in temperature, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or white blood cell count, and does not cause diarrhoea, cough, sleep disturbance, or rubbing of the ear or cheek, but that it does cause daytime restlessness, an increase in the amount of finger sucking or rubbing of the gum, an increase in drooling, and possibly some loss of appetite.

If the child is having extreme difficulty, the application of a non-irritating topical anaesthetic may bring temporary relief. The parent can apply the anaesthetic to the affected tissue over the erupting tooth three or four times a day. Several low-dose products specifically formulated for infants are available without pre- scription.

Caution must be exercised, however, when one is prescribing topical anaesthetics, especially for infants, because systemic absorption of the anaesthetic agent is rapid, and toxic doses can occur if the product is misused. The eruption process may be hastened if the child is allowed to chew on a piece of safe food item or a clean teething object.

To solve past pediatric dentistry exam questions, with correct answers and learn clincial rationales developed by our team using all the features that will aid you in productive, cluter free learning, visit our Solve Questions Page here

ERUPTION DIFFICULTIES

NATAL AND NEONATAL TEETH

Natal teeth are teeth present at birth, and “neonatal teeth” are teeth erupted within the first month of life. Premature eruption of a tooth at the time of birth or too early are accompanied by various difficulties, such as pain on suckling and refusal to feed, faced by the mother and the child due to the natal tooth/teeth. 85% of natal or neonatal teeth are mandibular primary incisors, and only small percentages. It is common for natal and neo- natal teeth to occur in pairs. Natal and neonatal molars are rare.

Studies suggest that the etiology for the premature eruption or the appearance of natal and neonatal teeth is multifactorial. A possible factor involving the early eruption of primary teeth seems to be familial, due to inheritance as an autosomal-dominant trait. Endocrine disturbance resulting from pituitary, thyroid, and gonads also may be one of the key factors.

Few syndromes are reported to be associated with natal teeth and neonatal teeth. These syndromes include Ellis-Van Creveld (Chondroectodermal Dysplasia) , Pachyonychia Congenital (Jadassohn-Lewandowsky), Hallermann-Streiff (Oculomandibulodyscephaly with Hypotrichosis) , Rubinstein-Taybi, Steatocystoma Multiplex, Pierre-Robin, Cyclopia, Pallister-Hall, Short Rib-Polydactyly (type II), Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch (Neonatal Progeria), Cleft Lip and Palate, Pfeiffer, Ectodermal Dysplasia, Craniofacial Dysostosis, Multiple Steatocystoma, Sotos, Adrenogenital, Epidermolysis-Bullosa Simplex including Van der Woude, Down’s Syndrome and Walker-Warburg Syndromes.

Most prematurely erupted teeth (immature type) are hypermobile because of limited root development. Some teeth may be mobile to the extent that there is danger of displacement of the tooth and possible aspiration, in which case the removal of the tooth is indicated. In some cases the sharp incisal edge of the tooth may cause laceration of the lingual surface of the tongue (Riga-Fede disease), and the tooth may have to be removed. The preferable approach, however, is to leave the tooth in place and to explain to the parents the desirability of maintaining this tooth in the mouth because of its importance in the growth and uncomplicated eruption of the adjacent teeth. Within a relatively short time the prematurely erupted tooth will become stabilized, and the other teeth in the arch will erupt

ERUPTION HEMATOMA (ERUPTION CYST)

A bluish-purple elevated area of tissue, commonly called an eruption hematoma, occasionally develops a few weeks before the eruption of a primary or permanent tooth. The blood-filled cyst is most frequently seen in the primary second molar or the first permanent molar region. This fact substantiates the belief that the condition develops as a result of trauma to the soft tissue during function

ERUPTION SEQUESTRUM

The eruption sequestrum is occasionally seen in children at the time of the eruption of the first permanent molar, overlying the crown of the tooth. Eruption sequestrum is composed of cementum like material formed within dental follicle. As the tooth erupts and the cusps emerge, the fragment sequestrates. Eruption sequestra are usually of little or no clinical significance. Some of these sequestra spontaneously resolve without noticeable symptoms. However, after an eruption sequestrum has surfaced through the mucosa, it may easily be removed if it is causing local irritation. Radiographic features may be available, mostly described as small round radiopacities just above the related crown. In most cases, the clinical and radiographic appearances have been considered strong enough to achieve the diagnosis of eruption sequestrum.

EPSTEIN PEARLS, BOHN NODULES, AND DENTAL LAMINA CYSTS

Multiple, small, white or grayish-white lesions on the alveolar mucosa of the newborn. Epstein pearls are formed along the midpalatine raphe. They are considered remnants of epithelial tissue trapped along the raphe as the fetus grew. Bohn nodules are formed along the buccal and lingual aspects of the dental ridges and on the palate away from the raphe. The nodules are considered remnants of salivary gland tissue and are histologically different from Epstein pearls. Dental lamina cysts are found on the crests of the maxillary and mandibular dental ridges. The cysts originate from remnants of the dental lamina. No treatment is indicated because the lesions are spontaneously shed a few weeks after birth.

Latest Posts

FREE PROMETRIC PRACTICE TESTS

Try out the most relevant Prometric mock test questions for Dental exams here.

ENROLL NOW